The

Williamsburg Dam failures.

On the morning of May 16, 1874 the huge earthen dam holding back a 100-acre water power reservoir three miles above Williamsburg on the East Branch of the Mill River failed catastrophically, causing vast destruction and the loss of 139 lives in the factory villages of Williamsburg, Skinnerville, Haydenville and Leeds. It was the worst disaster of its kind in North American history up to that time, and it made national news.

The event was such a sensation that many thousands of gawkers and souvenir-hunters descended on the ruined villages by the trainload, turning the misery of bereaved and destitute families into a tourist attraction and helping themselves to anything they could carry away. Photographers from all over New England arrived in the stricken valley to record the destruction in stereographs, then the primary medium for disseminating photographs to a national audience hungry for images. An estimated 500 different stereo images of the disaster's aftermath were shot by at least 14 different photographers, and most were very widely reproduced and distributed. The Meekins Library collection includes at least 84 different views, all mounted on heavy cards for use in handheld stereo viewers.

Emerging from a narrow, steep-sided valley just above the village, the river ordinarily flowed in a straight line southeastward about 300 yards, passing first Onslow Speman's button factory and then sliding between the saw and grist mills of William H. Adams to join the West Branch. At the confluence of the two branches, the larger river made a sharp bend eastward, flowing parallel to South Main Street and 200 feet north of it for 400 yards to pass on the north side of Henry L. James' woolen mill, before leaving the village on its course toward Skinnerville. When the flood came down the valley and hit Spelman's buttonshop, it was an avalanche of water, huge boulders and trees 30 feet deep and moving at close to 15 mph. It smashed the buttonshop and both mills instantly; the heavily timbered and triangulated clerestory roof of the buttonshop was left intact on the fringe of the flooded zone 400-500' from the factory site, but all other traces of the three buildings and their dams disappeared, down to the underlying bedrock. Continuing on its straight course toward the confluence with the West Branch, the flood gathered up half a dozen houses, their occupants, the ground they had stood on along Mill Street, and Mill Street itelf, and ignoring the old riverbed's left-hand bend to the east, it continued straight ahead across South Main Street.

On the opposite side of the street, Dr. and Mrs. Elbridge Johnson, their son and two daughters and the doctor's mother were at breakfast. Dr. Johnson had been an army surgeon during the Civil War, and had come to Williamsburg in the fall of 1865 to practice a more peaceful sort of medicine in a quiet country setting. The noise of the oncoming flood as it smashed mills and houses one after another, closer and closer in rapid succession, must have been like nothing that even Dr. Johnson had ever heard in battle, and we must assume the family leapt up from the table to see what was happening. Too late: their home was in the center of the path, and it was so completely obliterated that no trace of its foundation could later be found.

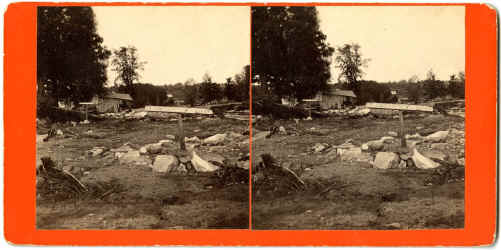

A few days after the flood, village minister John Gleason put up signs to help the surviving townspeople find, in a landscape suddenly barren and unfamiliar, the approximate locations of the dozens of houses that had vanished with their occupants. The sign pictured here reads 'Dr. Johnson - six drowned.' It was the largest loss of life in a single household in the village of Williamsburg, which lost 57 residents in all. The power of the flood was such that it carved an entirely new channel in which the river remained for months afterward, severing South Main Street toward Skinnerville. The river was eventually forced back into its old bed for the benefit of the Henry L. James woolen mill, which had ironically been left high, dry and powerless by floodwaters that had reached its second-story windows. When viewed in 3D, this image reveals a glimpse of the river flowing past the Johnson site in its new, flood-carved bed, at far right in the middle distance.

|