|

Cyrus Felix Demsey

Company A, Second Massachusetts Cavalry

contributed by Pat Johnson (descendent)

Cyrus Felix Demsey was born April 30, 1839, in Portsmouth, Ohio, second son of John and Tabitha (Duncan) Demsey. In 1853 his family left its home along the Ohio River and migrated to Macon County, Illinois, settling near the town of Decatur. John Demsey was a physician and his choice of profession would later have a profound effect on Cyrus, perhaps saving his life during the Civil War.

In 1859, at the age of nineteen Cyrus was ready to spread his wings and to join the others who were heading west to California. He enjoyed the active life and culture that San Francisco had to offer and by 1862 had joined the Pacific Coast Navy and was stationed at the United States Naval Yard at Mare Island. Word of the fall of Fort Sumter had marked the beginning of the War of the Rebellion, and was received with grave concern by the population of San Francisco. When the California Hundred was raised and headed east in 1862, Cyrus Demsey was a member.

In February of 1863, Companies A, B, C, D and K were detached for scouting, reconnaissance, picket duty, outpost duty and drill. Their first major action took place on June 26 at the South Anna Bridge, a railroad bridge twelve miles north of Richmond. In this encounter they were joined by the Eleventh Pennsylvania and part of the Twelfth Illinois Cavalry. A fierce engagement ensued, resulting in the capture of the bridge guard plus large quantities of army supplies and stores. One hundred twenty three prisoners were taken. Losses to Company A were one man killed and one man wounded.

Private Demsey met up with Mosby's Rangers on August 24, 1863. A thirty-man detail of Company A was enroute from Alexandria to Centerville with a herd of 100 horses. They had stopped to water the horses at Billy Goodling's Tavern on the Little River Turnpike near Fairfax Court House, ten miles west of Alexandria, when Mosby decided to capture or at least stampede as many of the horses as possible and so the skirmish began. The Federals, taken by surprise, ran for cover in and around the tavern. A lively battle ensued during which Mosby was wounded in the thigh and groin, injuries which would put him out of commission for about one month. By the end of the skirmish two members of Company A were killed, three wounded and nine captured. Cyrus was amongst those captured. He had spent his last day on the field of battle. Charles M Jenkins, a private of Company E, was captured also. These two men would spend the next fifteen months together fighting for survival in a number of Confederate prisons, and go on to spend the rest of their lives as close friends.

The prisoners were transferred 100 miles south to Libby Prison, located on the north side of the James River in Richmond. The brick warehouse prison consisted of three three-story buildings. The prisoners were confined to the top two floors of each building, six rooms in all. These were used for cooking, eating, washing, bathing and sleeping. At times there were more than 1000 men imprisoned in this limited space. When the prison was converted into an officers-only facility in October, Cyrus was moved to Belle Isle located in the James River in Richmond. This compound consisted of less than ten acres of land, swept in winter by cold winds off the river. It was a stockade-type prison where tents provided the shelter. As more and more prisoners arrived, there eventually were not enough tents to go around, so by the onset of winter only half of the 6,000 men had shelter. As a result, it was not uncommon for as many as twenty five men to die there in a single night.

There was also a severe shortage of food. The Confederate soldiers themselves were on limited rations and there was simply not enough food to go around. Early in the war, those captured were exchanged and thus the Union boys were sent back to the North. This practice was discontinued by 1863 and thereafter the prison populations simply got larger and larger. It was impossible to adequately feed all the prisoners. Disease was prevalent due to the living conditions and the weakened status of the men. Vermin were a constant scourge, conditions were filthy, and life was intolerable at times. For the most part the prisoners tried to make the best of it. They told stories, played games, sang and plotted ways in which they could escape. The men always expected to be exchanged, but that salvation never happened.

By 1864 the citizens of Richmond had become nervous about the large number of prisoners being housed in Richmond. There were worries that the Union forces, who were moving closer to Richmond, might enter the city, storm the prisons and free the Yankee prisoners. Eventually the decision was made to move all of the prIsoners out of Richmond. A new prison would be built farther south out of reach of the Union forces. The spot chosen for this new prison was near Americus, Georgia, and its construction started in late 1863. The prison was called Andersonville, a name that would come to epitomize the worst in the way of Civil War prisons.

The new facility was yet unfinished when it was decided to start moving the prisoners there beginning in early March of 1864. Each day 600 men were rounded up and taken away by train. Cyrus' turn came on March 22. The men were loaded onto cattle cars which were hot, unventilated and oppressive with the smell of their former residents. At the end of each day the men were allowed to disembark, stretch their legs and find a place on the ground to sleep. They were heavily guarded. The trip from Richmond took about a week and the men were exhausted upon their arrival at the new prison.

Andersonville was also a stockade-type prison. It was built on seventeen acres of land and was meant to house 8000 to 10,000 men. By June there were more than 22,000. There were no tents provided so the prisoners were left to their own devices to gather what they could find to build themselves makeshift shelters. During the summer ten acres were added to the enclosure but the prisoners kept coming and during August the total population had reached nearly 33,000. Condtitions here were extremely unsanitary. For one thing there was no fresh water. The small stream that bisected the stockade had already passed through the town of Andersonville and through the Confederate barracks. It served as both drinking and sewage water for the prison.

Death was common here, resulting from the polluted water, a shortage of food, bad sanitation, exposure, overcrowding and inadequate hospital facilities. The number of deaths for the month of August was 2933, the total number by the end of the war was nearly 13,000.

With so many dying we wonder how Cyrus made it through his six-month ordeal at Andersonville. Sometimes men survived due to some skill that they had, some service they could perform for the other prisoners in exchange for a portion of a food ration, part of a blanket or other necessities of life. It is quite possible that Cyrus' knowledge of the medical profession, learned from his father, gave him an edge in some way. We do know that Cyrus was of help to his friend, Charles Jenkins. In an affidavit provided by Dr. Cyrus Demsey for Mr. Jenkins' pension application after the War, Cyrus states, "I was his constant nurse for 13 months in Prison. (As a comrad)". This being the case, it is quite probable that Cyrus used his medical skills to aid other prisoners as well and to gain for himself some favors in exchange. Perhaps his attentiveness to others contributed to his own survival.

By the end of the summer, conditions at the stockade were at their worst. It was decided to move as many prisoners as possible out of Andersonville Prison. Starting in September detachments of prisoners were transferred to two new prisons. Cyrus was among the first ones to leave, traveling by railway north to Macon and then east to Camp Lawton, which was located in Millen, Georgia. By early November there were more than 10,000 prisoners at this stockade prison, most of them from Andersonville. Food and proper shelter were lacking here just as they had been at the other prisons.

Sherman's famous "march to the sea" brought a Union army straight towards Millen, and as it approached Camp Lawton, the Confederate authorities realized that they must do something quickly, or suffer grave consequences. There was certainly no way to counter the Union attack, and reprisals by the prisoners was another concern. They decided to transfer the prisoners to Savannah and release them there to the Union forces. As a result of this decision Cyrus was paroled on November 21, 1964, and delivered to Savannah the next day. By November 25 Cyrus had arrived at the College Green Barracks in Annapolis, Maryland, back at last on friendly ground.

Cyrus completed his enlistment on detached service and thus took part in no further military engagements. On April 12, 1865, the Civil War had finally ended. Three months later Cyrus Demsey was discharged from duty at Fairfax Court House, Virginia, along with his comrade and friend, Charles Jenkins. The date was July 20, 1865.

After the close of the war Cyrus returned to his family home in Illinois where he followed in his father's footsteps to pursue a career in medicine. He was married in 1868 to Eliza Gouge. Their marriage produced twin sons who died in infancy and another son who lived to maturity. Eliza died in 1872. Cyrus then married Clarinda Gates and they became parents of a son and daughter.

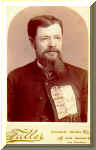

In the summer of 1886 Cyrus had the opportunity to travel to San Francisco for a reunion of the California Hundred and Battalion. He decided at the same time to move his family to the West Coast. The reunion was preceded by the Twelfth Annual Session of the Grand Army of the Republic (the GAR), whose meetings began August 4, 1886. Its principal objectives in the early years involved the creation of state veterans' homes for the disabled. In 1881 the GAR Posts in California made appeals to the public and gave fundraisers in order to raise money for a Soldiers' and Sailors' Home in their state. Thirty nine thousand dollars was raised. With a portion of this money a tract of land containing 910 acres was purchased near Yountville in Napa County at a cost of $17,750. Early in 1883 construction began and the Home was opened in April, 1884. The men who managed the facility at that time were veterans of the California Hundred. Cyrus presented a photograph of himself to the Home. Its inscription read, "Presented to Yountville Veterans Home By C.F. Demsey, M.D., Comrade of Calif. 100. Co A 2nd Mass. Cav."

Cyrus and his family made San Francisco their home for about a year then moved to Southern California. Cyrus set up his medical practice in San Buenaventura in 1887 and remained there until the late 1890s. He then relocated in the desert town of Mojave, serving the workers and families of the Southern Pacific and Santa Fe Railroads.

In January of 1901 Cyrus' wife Clarinda died. Cyrus continued his residence in Mojave and in 1903 married Matilda Kern who bore him one daughter. The three of them lived happily in Mojave until Cyrus' death on March 27, 1913. His remains are held at the Chapel of The Pines Columbarium in Los Angeles.

|